In Angular, directives can have an isolate scope that creates an inner scope that is separated from the outer scope. There are a variety of options for mapping the outer scope to the inner scope, and this can often be a source of confusion. Recently, I’ve noticed a ton of up-votes for my answer to the Stackoverlow question: Differences among = & @ in Angular directive scope?

I created a simple jsFiddle to answer the question. The HTML markup looks like this:

<div ng-app="myApp" ng-controller="myController">

<div>Outer bar: {{bar}}</div>

<div>Status: {{status}}</div>

<my-directive foo="bar"

literal="bar"

behavior="a+b"

call="update(1,val)" /> </div>

The code behind it:

var app = angular.module("myApp", []); app.controller("myController", function ($scope) {

$scope.status = 'Ready.';

$scope.a = 1;

$scope.b = 2;

$scope.bar = 'This is bar.';

$scope.update = function (parm1, parm2) {

$scope.status = parm1 + ": " + parm2;

}; }); app.directive("myDirective", function () {

return {

restrict: 'E',

scope: {

foo: '=',

literal: '@',

literalBehavior: '@behavior',

behavior: '&',

call: '&'

},

template: '<div>Inner bar: {{foo}}</div>' +

'<div>Inner literal: {{literal}}</div>' +

'<div>Literal Behavior: {{literalBehavior}}</div>' +

'<div>Result of behavior(): {{result}}</div>',

link: function (scope) {

scope.foo = scope.foo + " (modified by directive).";

scope.result = scope.behavior();

scope.call({ val: 99 });

}

}; });

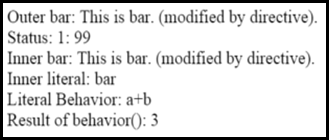

With the following result:

To break down what is happening, I offer the following explanation that I hope will help to clarify how isolate scope works. Please note that although for the sake of illustration I’m using $scope, this works equally well with the controller as approach that I recommend.

Bindings

if your directive looks like this:

<my-directive target="foo" />

Then you have these possibilities for scope:

{ target: '=' }

This will bind scope.target (directive) to $scope.foo (outer scope). This is because = is for two-way binding and when you don't specify anything, it automatically matches the name on the inner scope to the name of the attribute on the directive. Changes to scope.target will update $scope.foo.

{ bar: '=target' }

This will bind scope.bar to $scope.foo. This is because again we specify two-way binding, but tell the directive that what is in the attribute "target" should appear on the inner scope as "bar". Changes to scope.bar will update $scope.foo.

{ target: '@' }

This will set scope.target to "foo" because @ means "take it literally." Changes to scope.target won't propagate outside of your directive.

{ bar: '@target' }

This will set scope.bar to "foo" because @ takes it's value from the target attribute. Changes to scope.bar won't propagate outside of your directive.

Behaviors

Now let's talk behaviors. Let's assume your outer scope has this:

$scope.foo = function(parm1, parm2) {

console.log(parm1 + ": " + parm2); }

There are several ways you can access this. If your HTML is:

<my-directive target='foo'>

Then

{ target: '=' }

Will allow you to call scope.target(1,2) from your directive.

Same thing,

{ bar: '=target' }

Allows you to call scope.bar(1,2) from your directive.

The more common way is to establish this as a behavior. Technically, ampersand evaluates an expression in the context of the parent. That's important. So I could have:

<my-directive target="a+b" />

And if the parent scope has $scope.a = 1 and $scope.b = 2, then on my directive:

{ target: '&' }

I can call scope.target() and the result will be 3. This is important - the binding is exposed as a function to the inner scope but the directive can bind to an expression.

A more common way to do this is:

<my-directive target="foo(val1,val2)">

Then you can use:

{ target: '&' }

And call from the directive:

scope.target({ val1: 1, val2: 2 });

This takes the object you passed, maps the properties to parameters in the evaluated expression and then calls the behavior, this case calling $scope.foo(1,2);

You could also do this:

<my-directive target="foo(1, val)" />

This locks in the first parameter to the literal 1, and from the directive:

{ bar: '&target' }

Then:

scope.bar(5)

Which would call $scope.foo(1,5);

Summary

As you can see, scope isolation is a very powerful mechanism. When used correctly it enables you to reuse a directive and protect the parent scope from side effects, while allowing you to pass important attributes and bindings as necessary. Understanding this will be a tremendous benefit for you when authoring custom directives.

As always, your thoughts and feedback are appreciated!